Browse Documents By...

Original Language...

Documents For...

Browse Commentaries By...

Browse Referred Persons By...

Court of Cassation on sculptures, Paris (1814)

Source: Bibliothèque universitaire de Poitiers (SCD) : Recueil général des lois et des arrêts (Recueil Sirey), 1er série 1791-1830, 4e volume - 1812-1814

Citation:

Court of Cassation on sculptures, Paris (1814), Primary Sources on Copyright (1450-1900), eds L. Bently & M. Kretschmer, www.copyrighthistory.org

Back | Record | Images | Commentaries: [1]

Translation only | Transcription only | Show all | Bundled images as pdf

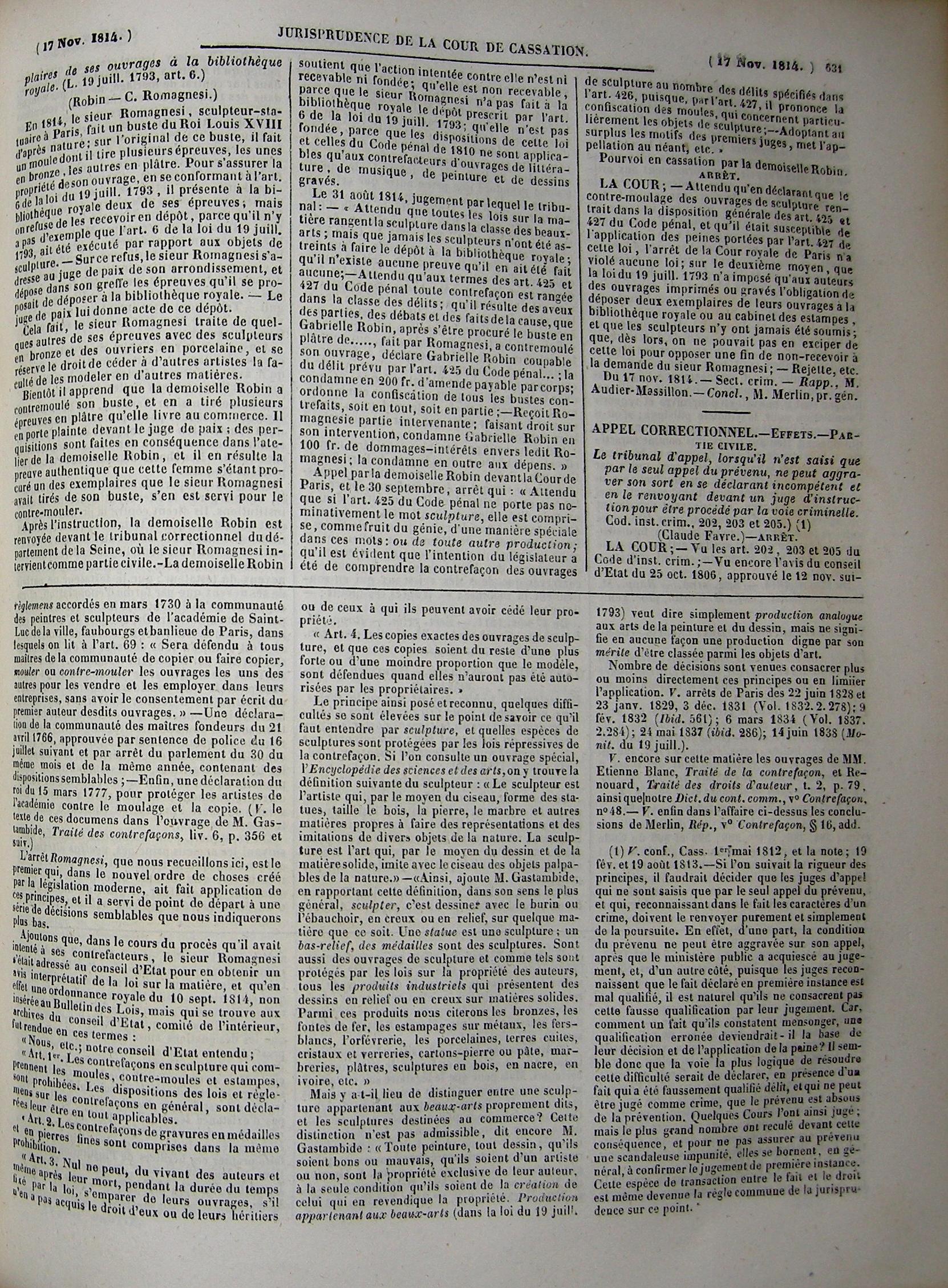

(17 Nov. 1814) JURISPRUDENCE OF THE COURT OF CASSATION (17 Nov. 1814) 631

______________________________

of his works at the Royal Library.

(L[aw] of 19th July 1793, art. 6.)

(Robin v. Romagnesi)

In 1814, the Paris-based sculptor and statuary,

M. Romagnesi, made a bust of King Louis XVIII

after life: from the original of this bust he made a

mould from which he cast several copies, some

in bronze, others in plaster. To safeguard his

property in the work [ouvrage] and in conformity

with article 6 of the law of 19th July 1793 he

presented the royal library with two copies of his

casts; but their deposit was refused because

there was no precedent of article 6 of the law

of 19th July 1793 having been executed in relation

to objects of sculpture. – Following this refusal,

M. Romagnesi addressed himself to the justice of

the peace in his district & deposited the copies

he had intended for the Royal Library in the office

of his clerk. – The justice of the peace

gave him formal acknowledgement of the deposit.

Having done this, M. Romagnesi sold casts

to some other sculptors in bronze & to porcelain makers,

reserving for himself the right to cede to other artists

the right to cast them in other materials.

He soon learned that Mlle Robin had

counter-cast his bust, and had produced from it [the mould]

several plaster casts which she put on sale. He lodged

a complaint about it with the justice; in the wake of this,

searches were carried out in Mlle Robin's workshop

from which emerged reliable proof that this woman, having

obtained one of the casts that M. Romagnesi had made

from his own bust, had used it to counter-cast hers.

Following the investigation, Mlle Robin was sent

before the Criminal Court of the département of

the Seine, in which M. Romagnesi took action as a

plaintiff [partie civile]. – Mlle Robin

[2nd column:]

maintained that the action brought against her was

neither valid nor justified; it was not valid because

M. Romagnesi had not made the requisite deposit

at the Royal Library according to article 6 of the law

of 19 July 1793; not justified because the remit of the

law & that of the 1810 Code pénal only applied

to those who counterfeited works of literature, music

and painting and drawing in printed reproduction.

The judgement of 31 August 1814 by which the

Court [resolved]: «Whereas all the laws on this matter

place sculpture in the class of the fine arts; but

sculptors have never been obliged to deposit their works at

the Royal Library; and there is no evidence that they

have ever done so; whereas according to the

terms of art. 425 & 427 of the Code pénal all counterfeits

are ranked in the class of offences; and it emerges from the

statements of both parties, & from the debates & facts of

the case, that Gabrielle Robin, after having procured

the plaster bust... by Romagnesi, had counter-moulded

his work; Gabrielle Robin is declared guilty of the

offence envisaged by art. 425 of the Code pénal; sentenced to

a fine of 200 francs, payable in a lump sum; ordered

the confiscation of all the busts counter-cast either in

part or in whole; - Upheld Romagnesi's case; finding in

his favour, sentences Gabrielle Robin to 100 francs in

damages and interest against the said Romagnesi; sentences her,

moreover, to pay the legal expenses. »

Appeal by Mlle Robin before the Court of

Paris; and decreed on 30 September: «Whereas if

art. 425 of the Code pénal does not explicitly

contain the word sculpture, it is implicit, as a fruit

of genius, in the special meaning of the words: or

of all other production; and it is clear that the intention

of the legislator had been to include the counterfeiting of works

[3rd column:]

of sculpture in the offences specified by art. 426, since,

by art. 427, he ordered the confiscation of moulds

which primarily relate to objects of sculpture; – Thus

adopting the intention of the first judges the appeal

is dismissed, etc. »

Judged on appeal [cassation] against Mlle Robin.

RULING.

THE COURT; – Whereas in declaring

the counter-casting of works of sculpture to fall

under the general remit of articles 425 and 427 of

the Code pénal, and that it was susceptible of

application of the penalties specified by

art. 427 of this law, the decree of the Royal Court

of Paris has not breached any law; whereas, with

regard to the second count, the law of 19 July,

1793, only obliged the authors of printed and

engraved works to deposit copies of these works

at the Royal Library, and sculptors have never

been subject to this requirement; and whereas,

consequently, one could not make an exception

of that law in order to advance an argument of

no-case-to-answer in opposition to M. Romagnesi's

demands; – Case rejected etc.

17th Nov. 1814. – Criminal Division. – Reported by: M.

Audier-Massillon . – Concl., M. Merlin, Attorney-General.

______________

regulations granted in March 1730 to the Guild of Painters and Sculptors of the Académie de

Saint-Luc of the city, suburbs and precincts of Paris, in which art. 69 states that: «All masters of the guild are

forbidden to copy or cause to have copied, cast or counter-cast the works of one

another, in order to sell them and use them for their projects, without having the written consent of the first author of

the said works.» – One declaration of the Guild of Master Founders on 21 April 1766, approved by sentence

de police on 16 July of that year and by a Ruling of the Parlement on the 30th of the same

month and the same year, containing similar provisions; – Finally, a Royal declaration of 15 March 1777, for

protecting the artists of the Academy against casting and copying. (See the text of these documents in M.

Gastambide's Traité des contrefaçons, vi, p.356f.)

The sentence in the Romagnesi case, which we are citing here, is the first which, in the new

system created by the modern legislation, has applied these principles, and it has served as the point of departure for a

number of similar decisions which we will mention further below.

We should add that in the course of the legal proceedings which he instituted against his counterfeiters,

M. Romagnesi addressed himself to the Council of State, in order to obtain an opinion providing an

interpretation of the law in this matter, and that as a result a Royal ordinance of 10 Sept. 1814, which is not included

in the Bulletin des Lois, but which can be found in the archives of the Council of State, Committee

for the Interior, was issued in these terms:

«We, etc.; by which our Council of State is understood;

«Art. 1. Counterfeits in the realm of sculpture, which consist of moulds, counter-casts and engravings, are

forbidden. The provisions of the laws and regulations on counterfeiting in general are declared to also apply in all

respects to the former.

«Art. 2. Counterfeits consisting of engravings of medals and gemstones are covered by the same prohibition.

«Art. 3. Whilst the authors are still alive and even after their death, no one may, in the space of time fixed by the

law, take possession of [s'emparer de] their works, unless that person has acquired the right to them

from the authors or their heirs, or from those to whom the former may have ceded their property right.

«Art. 4. Identical copies of works of sculpture, regardless of whether these copies are made on a larger or a

smaller scale in relation to the prototype, are forbidden unless they have been authorised by the property-holders

[propriétaires].»

The principle having been settled and recognized thus, some difficulties presented themselves with regard to

establishing what one was supposed to understand by sculpture, and what types of sculptures were

protected by the laws that punished counterfeiting. If one consults a specialist work, the Encyclopédie des

sciences et des arts, the following definition of a sculptor is given there: «A sculptor is an artist who, by

means of the chisel, shapes statues, carves wood, stone, marble and other materials suitable for making

representations and imitations of various objects of nature. Sculpture is the art which, by means of design and solid

matter, imitates with the chisel, the tangible objects of nature.» – «Thus», M. Gastambide adds, when citing this

definition; «in its most general sense, sculpting means to design with the burin or the great chisel

[ébauchoir], en creux or in relievo, on any material whatsoever. A

statue is a sculpture; a bas-relief, medals are all sculptures. Also

classed as sculptures and protected as such by the laws on the property of authors, are all industrial

products which display designs in relievo or en creux on solid materials. Amongst such

products we shall cite bronze figures, iron casts, engravings on metals, tin-plates, goldsmith's work, porcelains,

ceramics, crystals and glass-work, stone and paste cards, marble grinding work, plaster figures, sculptures in wood,

mother-of-pearl, ivory, etc.»

But is it appropriate to distinguish between a sculpture belonging to the fine arts proper, and the

sculptures which are meant for commerce? This distinction is not acceptable, says once again M. Gastambide: «All

paintings, all drawings, regardless of whether they are good or bad, of whether they are the work of an artist or not,

are the exclusive property of their author, on the sole condition that they should have been created by

the person who claims them as his property. Production within the domain of the fine arts (in the law

of 19 July 1793) means simply production analogous to the arts of painting and drawing, but does not

in any way imply a production which, on account of its merit, is considered worthy of being classed

amongst the objects of art.»

A number of decisions have been pronounced which, more or less directly, confirm these principles or delimit

the scope of their application. See the rulings of the Court of Paris of 22 June 1828 and 23 Jan. 1829, 3 Dec. 1831; 9

February 1832; 6 March 1834; 24 May 1837; 14 June 1838.

On this subject, see also the works of Messrs. Etienne Blanc, Traité de la contrefaçon, and

Renouard, Traité des droits d'auteur, ii, p.79, as well as our Dict. du cont. comm., vº

Counterfeiting, nº 48. – See, finally, on the above case the conclusions of Merlin,

Rép., vº Counterfeiting, § 16.

No Transcription available.

Source: Bibliothèque universitaire de Poitiers (SCD) : Recueil général des lois et des arrêts (Recueil Sirey), 1er série 1791-1830, 4e volume - 1812-1814

Citation:

Court of Cassation on sculptures, Paris (1814), Primary Sources on Copyright (1450-1900), eds L. Bently & M. Kretschmer, www.copyrighthistory.org

Back | Record | Images | Commentaries: [1]

Translation only | Transcription only | Show all | Bundled images as pdf

______________________________

of his works at the Royal Library.

(L[aw] of 19th July 1793, art. 6.)

(Robin v. Romagnesi)

In 1814, the Paris-based sculptor and statuary,

M. Romagnesi, made a bust of King Louis XVIII

after life: from the original of this bust he made a

mould from which he cast several copies, some

in bronze, others in plaster. To safeguard his

property in the work [ouvrage] and in conformity

with article 6 of the law of 19th July 1793 he

presented the royal library with two copies of his

casts; but their deposit was refused because

there was no precedent of article 6 of the law

of 19th July 1793 having been executed in relation

to objects of sculpture. – Following this refusal,

M. Romagnesi addressed himself to the justice of

the peace in his district & deposited the copies

he had intended for the Royal Library in the office

of his clerk. – The justice of the peace

gave him formal acknowledgement of the deposit.

Having done this, M. Romagnesi sold casts

to some other sculptors in bronze & to porcelain makers,

reserving for himself the right to cede to other artists

the right to cast them in other materials.

He soon learned that Mlle Robin had

counter-cast his bust, and had produced from it [the mould]

several plaster casts which she put on sale. He lodged

a complaint about it with the justice; in the wake of this,

searches were carried out in Mlle Robin's workshop

from which emerged reliable proof that this woman, having

obtained one of the casts that M. Romagnesi had made

from his own bust, had used it to counter-cast hers.

Following the investigation, Mlle Robin was sent

before the Criminal Court of the département of

the Seine, in which M. Romagnesi took action as a

plaintiff [partie civile]. – Mlle Robin

[2nd column:]

maintained that the action brought against her was

neither valid nor justified; it was not valid because

M. Romagnesi had not made the requisite deposit

at the Royal Library according to article 6 of the law

of 19 July 1793; not justified because the remit of the

law & that of the 1810 Code pénal only applied

to those who counterfeited works of literature, music

and painting and drawing in printed reproduction.

The judgement of 31 August 1814 by which the

Court [resolved]: «Whereas all the laws on this matter

place sculpture in the class of the fine arts; but

sculptors have never been obliged to deposit their works at

the Royal Library; and there is no evidence that they

have ever done so; whereas according to the

terms of art. 425 & 427 of the Code pénal all counterfeits

are ranked in the class of offences; and it emerges from the

statements of both parties, & from the debates & facts of

the case, that Gabrielle Robin, after having procured

the plaster bust... by Romagnesi, had counter-moulded

his work; Gabrielle Robin is declared guilty of the

offence envisaged by art. 425 of the Code pénal; sentenced to

a fine of 200 francs, payable in a lump sum; ordered

the confiscation of all the busts counter-cast either in

part or in whole; - Upheld Romagnesi's case; finding in

his favour, sentences Gabrielle Robin to 100 francs in

damages and interest against the said Romagnesi; sentences her,

moreover, to pay the legal expenses. »

Appeal by Mlle Robin before the Court of

Paris; and decreed on 30 September: «Whereas if

art. 425 of the Code pénal does not explicitly

contain the word sculpture, it is implicit, as a fruit

of genius, in the special meaning of the words: or

of all other production; and it is clear that the intention

of the legislator had been to include the counterfeiting of works

[3rd column:]

of sculpture in the offences specified by art. 426, since,

by art. 427, he ordered the confiscation of moulds

which primarily relate to objects of sculpture; – Thus

adopting the intention of the first judges the appeal

is dismissed, etc. »

Judged on appeal [cassation] against Mlle Robin.

RULING.

THE COURT; – Whereas in declaring

the counter-casting of works of sculpture to fall

under the general remit of articles 425 and 427 of

the Code pénal, and that it was susceptible of

application of the penalties specified by

art. 427 of this law, the decree of the Royal Court

of Paris has not breached any law; whereas, with

regard to the second count, the law of 19 July,

1793, only obliged the authors of printed and

engraved works to deposit copies of these works

at the Royal Library, and sculptors have never

been subject to this requirement; and whereas,

consequently, one could not make an exception

of that law in order to advance an argument of

no-case-to-answer in opposition to M. Romagnesi's

demands; – Case rejected etc.

17th Nov. 1814. – Criminal Division. – Reported by: M.

Audier-Massillon . – Concl., M. Merlin, Attorney-General.

______________

regulations granted in March 1730 to the Guild of Painters and Sculptors of the Académie de

Saint-Luc of the city, suburbs and precincts of Paris, in which art. 69 states that: «All masters of the guild are

forbidden to copy or cause to have copied, cast or counter-cast the works of one

another, in order to sell them and use them for their projects, without having the written consent of the first author of

the said works.» – One declaration of the Guild of Master Founders on 21 April 1766, approved by sentence

de police on 16 July of that year and by a Ruling of the Parlement on the 30th of the same

month and the same year, containing similar provisions; – Finally, a Royal declaration of 15 March 1777, for

protecting the artists of the Academy against casting and copying. (See the text of these documents in M.

Gastambide's Traité des contrefaçons, vi, p.356f.)

The sentence in the Romagnesi case, which we are citing here, is the first which, in the new

system created by the modern legislation, has applied these principles, and it has served as the point of departure for a

number of similar decisions which we will mention further below.

We should add that in the course of the legal proceedings which he instituted against his counterfeiters,

M. Romagnesi addressed himself to the Council of State, in order to obtain an opinion providing an

interpretation of the law in this matter, and that as a result a Royal ordinance of 10 Sept. 1814, which is not included

in the Bulletin des Lois, but which can be found in the archives of the Council of State, Committee

for the Interior, was issued in these terms:

«We, etc.; by which our Council of State is understood;

«Art. 1. Counterfeits in the realm of sculpture, which consist of moulds, counter-casts and engravings, are

forbidden. The provisions of the laws and regulations on counterfeiting in general are declared to also apply in all

respects to the former.

«Art. 2. Counterfeits consisting of engravings of medals and gemstones are covered by the same prohibition.

«Art. 3. Whilst the authors are still alive and even after their death, no one may, in the space of time fixed by the

law, take possession of [s'emparer de] their works, unless that person has acquired the right to them

from the authors or their heirs, or from those to whom the former may have ceded their property right.

«Art. 4. Identical copies of works of sculpture, regardless of whether these copies are made on a larger or a

smaller scale in relation to the prototype, are forbidden unless they have been authorised by the property-holders

[propriétaires].»

The principle having been settled and recognized thus, some difficulties presented themselves with regard to

establishing what one was supposed to understand by sculpture, and what types of sculptures were

protected by the laws that punished counterfeiting. If one consults a specialist work, the Encyclopédie des

sciences et des arts, the following definition of a sculptor is given there: «A sculptor is an artist who, by

means of the chisel, shapes statues, carves wood, stone, marble and other materials suitable for making

representations and imitations of various objects of nature. Sculpture is the art which, by means of design and solid

matter, imitates with the chisel, the tangible objects of nature.» – «Thus», M. Gastambide adds, when citing this

definition; «in its most general sense, sculpting means to design with the burin or the great chisel

[ébauchoir], en creux or in relievo, on any material whatsoever. A

statue is a sculpture; a bas-relief, medals are all sculptures. Also

classed as sculptures and protected as such by the laws on the property of authors, are all industrial

products which display designs in relievo or en creux on solid materials. Amongst such

products we shall cite bronze figures, iron casts, engravings on metals, tin-plates, goldsmith's work, porcelains,

ceramics, crystals and glass-work, stone and paste cards, marble grinding work, plaster figures, sculptures in wood,

mother-of-pearl, ivory, etc.»

But is it appropriate to distinguish between a sculpture belonging to the fine arts proper, and the

sculptures which are meant for commerce? This distinction is not acceptable, says once again M. Gastambide: «All

paintings, all drawings, regardless of whether they are good or bad, of whether they are the work of an artist or not,

are the exclusive property of their author, on the sole condition that they should have been created by

the person who claims them as his property. Production within the domain of the fine arts (in the law

of 19 July 1793) means simply production analogous to the arts of painting and drawing, but does not

in any way imply a production which, on account of its merit, is considered worthy of being classed

amongst the objects of art.»

A number of decisions have been pronounced which, more or less directly, confirm these principles or delimit

the scope of their application. See the rulings of the Court of Paris of 22 June 1828 and 23 Jan. 1829, 3 Dec. 1831; 9

February 1832; 6 March 1834; 24 May 1837; 14 June 1838.

On this subject, see also the works of Messrs. Etienne Blanc, Traité de la contrefaçon, and

Renouard, Traité des droits d'auteur, ii, p.79, as well as our Dict. du cont. comm., vº

Counterfeiting, nº 48. – See, finally, on the above case the conclusions of Merlin,

Rép., vº Counterfeiting, § 16.

No Transcription available.