PRIMARY SOURCES

ON COPYRIGHT

(1450-1900)

Petition from and Privilege granted to Antonio Tempesta for a map of Rome (1593)

Back | Commentary info | Commentary

Printer friendly version

This work by www.copyrighthistory.org is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Primary Sources on Copyright (1450-1900)

Identifier: va_1593

Commentary on Petition from and Privilege granted to Antonio Tempesta for a map of Rome (1593)

Jane C. Ginsburg

Please cite as:

Ginsburg, J.C. (2022) ‘Commentary on Petition from and Privilege granted to Antonio Tempesta for a map of Rome (1593)', in Primary Sources on Copyright (1450-1900), eds L. Bently & M. Kretschmer, www.copyrighthistory.org

1. Image: Antonio Tempesta

2. Antonio Tempesta’s Petition

3. Tempesta’s privilege

4. Justifications for privileges

5. Persons mentioned in the petition and privilege

1. Image

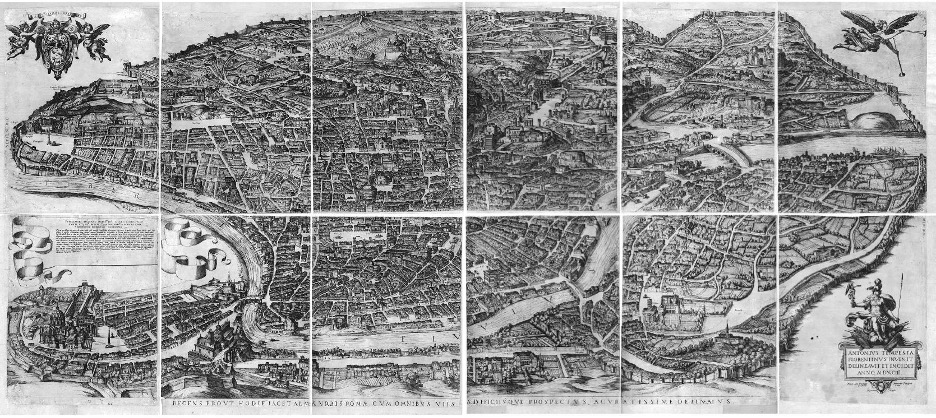

Antonio Tempesta, Recens prout hodie iacet almae urbis Romae cum omnibus viis aedificiisque prospectus accuratissime delineatus (Rome, 1593), etching, 40¾ × 96 in. (103.5 × 244 cm). Photo: Newberry Library, Chicago, Novacco 4F 256. Image copied from Jessica Maier, Rome Measured and Imagined: Early Modern Maps of the Eternal City (U Chicago Press 2015), fig 57.

2. Antonio Tempesta’s Petition

Antonio Tempesta was by no means the first mapmaker or printmaker of Roman images to seek exclusive rights from the Pope and other sovereigns. For example, Leonardo Bufalini received Papal and French, Spanish and Venetian privileges for his 1551 map of Rome; in 1587 Venetian publisher Girolamo Franzino obtained a Papal privilege for Le cose maravigliose dell'alma città di Roma, with text and engravings celebrating the great public works of Sixtus V; in 1588 Flemish publisher Nicolas van Aelst (who would publish other prints by Tempesta) received a Papal privilege for engravings of Roman obelisks. But Tempesta’s map was exceptionally monumental (his design used twelve folio sheets to depict in bird’s-eye view, in great detail, the city of Rome stretching out to the north-west as one might see it from the Janiculum, which stands in the city’s south-eastern corner), and his Papal privilege stands out for the arguments Tempesta made to support his application for the grant.

Tempesta’s petition evokes justifications spanning the full range of modern intellectual property rhetoric, from fear of unscrupulous competitors, to author-centric rationales. Invocations of labor and investment (“with much personal expense, effort, and care for many years”), and unfair competition-based justifications (“fearing that others may usurp this work from him by copying it, and consequently gather the fruits of his efforts”) were familiar – indeed ubiquitous – in Tempesta’s time, and still echo today. From the earliest Roman printing privileges in the late 15th century, these rationales figured prominently in petitions by and privileges granted both to authors and to publishers. Frequently, petitions for Papal privileges and the ensuing Papal privileges would emphasize the public benefit that publishing the work would confer, while stressing that the author or publisher hesitates to bring the work forth, lest others unfairly reap the fruits of their labors, to the great detriment of the author or publisher. Other petitions for Papal privileges make explicit the incentive rationale that underlies investment-protection arguments. They urge, as did Tempesta, that the grant of a privilege would encourage not only immediate publication of the identified work, but also future productivity, to even greater public benefit (“so that he may with so much greater eagerness attend to and labor every day [to create] new things for the utility of all”). The Papal printing privilege regime well understood printing monopolies to be incentives to intellectual and financial investment, a rationale with which we today recognize as one of the philosophical pillars of modern copyright law.

Tempesta’s petition, however, goes further than its antecedents with respect to the second pillar of modern copyright law, the natural rights of the author, a rationale that roots exclusive rights in personal creativity. Tempesta’s contention that new works routinely receive privileges, implying “ought” (for his work) from “is” (for works in general), was not novel. But he focused the rights on the creator (“as is usually granted to every creator of new works”), and equated creativity with his personal honor, thus foreshadowing a moral rights conception of copyright. It would be anachronistic to argue that Tempesta claimed that exclusive rights inherently arise out of the creation of a work of authorship (rather than solely by sovereign grant); on the contrary, Tempesta carefully acknowledged both that privileges are a “singular grace” from the Pope, and that all works must receive a license from the Papal censors.

Nonetheless, in advancing the then-unusual request that the privilege cover “all other works that the Petitioner shall in the future create or publish,” Tempesta was urging that his entire future production should automatically enjoy a ten-year monopoly on reproduction and distribution in the Papal States (subject, of course, to the censors’ approval of each work Tempesta would bring forth). In more modern terms, Tempesta was seeking a result equivalent to “you create it, it’s yours.” Tempesta also tied his request to incentive rationales – the broad grant would spur him ever more eagerly to greater creativity, but even this conflation of creativity-based and labor-incentive conceptions, one might contend, anticipates the frequent oscillation and overlap in modern copyright between natural rights and social contractarian theories of copyright.

3. Tempesta’s privilege

Sec. Brev. Reg. 208 F. 74 includes two versions of the same privilege granted to Antonio Tempesta in October 1593. The text found on pages 74r-74v is a finalized version of the text found on pages 75r-75v, which features heavy handwritten edits between the lines and in the margins.

The privilege that Clement VIII in fact granted to Tempesta, while very broad, fell short of the full range of Tempesta’s aspiration. The Pope did not cover all of Tempesta’s future print production, but he did grant exclusive rights not only in the map of Rome, but “also in maps of whatever other places and cities that he will invent and will have engraved onto copper plates.” (It does not appear, however, that Tempesta in fact created maps, large-scale or otherwise, of other cities or locations.) Moreover, the scope of the monopoly in the map of Rome (and, potentially, of other locations) extended to what copyright lawyers today call “derivative works,” that is, works based on the protected source, such as adaptations and new editions. The privilege thus reached “whatsoever form, whether larger or smaller, or in any form different from the version initially printed.” Coverage of different size versions of the map would ensure Tempesta control over smaller, less expensive, editions, whether to exploit that market, or, as appears to be the case, to preserve the monumental cachet of the immense original against the publication of low-end editions.

Tempesta’s privilege thus served multiple purposes. It allowed him to control the market for his work, matching the public for his map to his self-conception as an innovative painter-printmaker, a polyvalent artist who not only “invents” the image, but “with his own hand” prepares it for the print medium, and moreover executes the transfer of the drawing to the copper plate.

The exclusive rights the privilege conveyed provided legal security sufficient to warrant the undertaking of creating and disseminating the map and, Tempesta asserted, stimulating further creative endeavors. And it enhanced the author’s “honor” by conferring the prestige of the approval of the Pope and other sovereigns, a prestige that carried market value, as attested by the persistent appearance of the original notice of “privileges of the highest princes” (cum privilegiis summorum principum) through the 1645 reprinting of the map, long after the original privileges would have expired.

4. Justifications for privileges

Tempesta’s petition may voice the most comprehensive and “modern” set of justifications for copyright, but many 16th-century petitions echo several of the arguments found in Tempesta’s petition. The following chart details justifications, in descending order of occurrence expressed in the documents I have found in the Vatican Secret archives.

|

Justification |

Author |

Printer |

Total |

|

Unfair Competition |

118 |

80 |

198 |

|

Public Benefit |

74 |

59 |

133 |

|

Labor and Expense |

62 |

46 |

108 |

|

Accuracy |

17 |

20 |

37 |

|

Creation of new matter |

24 |

9 |

33 |

|

“Usual” Privilege |

17 |

10 |

27 |

|

Skill/Merit |

14 |

4 |

18 |

|

Consent of Author |

4 |

10 |

14 |

|

Patronage |

7 |

5 |

12 |

|

Expedite |

6 |

3 |

9 |

|

Approval by Censor |

4 |

2 |

6 |

|

Poverty |

4 |

2 |

6 |

|

Scarcity of Copies |

0 |

5 |

5 |

|

Future Works |

2 |

2 |

4 |

|

Prior Privilege |

0 |

5 |

5 |

|

Honor |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|

Total |

354 |

239 |

617 |

The most frequent justifications for the grant of a privilege advert to the labor and expense invested in the work, and the fear that, absent exclusive rights, unscrupulous printers will unfairly reap the fruits of the author’s or printer’s endeavors. The second most often-occurring justification urges the public benefit that will flow from the publication of the work; the Papal privilege variant on this general theme emphasized the importance to Catholic doctrine of disseminating the works in question. Of course, works could be published without a privilege, and perhaps would achieve wider distribution if their authors or printers did not assert control over their circulation. Hence the importance of a third justification: the privilege will not only recognize the effort and expense invested in a work, but will reward the care the author or printer have taken to ensure the work’s accuracy (and conformity to Church doctrine). For example, Martin Zuria, the nephew and literary executor of the Spanish canon lawyer Martin de Azpilcueta, in 1586 requested a world-wide privilege because he would “spare no expense or effort so that the said works would emerge well-ordered and well-printed with summaries, reference numbers, and other diligent emendations as required, and because booksellers intent only on making money do not bestow the care needed for the perfection of the said works and instead print them in any way they please, not without detriment to the public interest.”

See Sec. Brev. Reg. 122 F 528 (petition) (Sept. 3, 1586). See also Sec. Brev. Reg. 140 F 314 (Apr. 22, 1589) (privilege granted to Gerard Voss for his translations and editions of works of St Ephrem), https://www.copyrighthistory.org/cam/tools/request/showRecord.php?id=record_va_1589 (Petitions from and Privilege granted to Gerard Voss for his Latin translation of the works of St. Ephrem of Syria.) Or Giulio Calvi, a cleric of Frascati, who sought a privilege for a compendium of excerpts of the writings of St Thomas Aquinas; his work is “very useful to the church of God, and because others might publish it with some additions which do not correspond to the sincere and true doctrine of Aquinas, in the way the petitioner has diligently followed it.” Sec. Brev. Reg. 293 F 113 (Mar. 6, 1600). While many petitions stress the utility of accurate versions to scholars, popular piety was an important goal as well. Hence appeals not only to the works’ benefit to “all Christians,” but also “to women and ignorant people.” Sec. Brev. Reg. 217 F 216 (petition) (July 21, 1594). See petition of Venetian printer Giovanni Varisco for a privilege on printing “the mass of the most Blessed Madonna as revised according to the second Council of Trent with Latin and vernacular headings for the greater understanding of women and ignorant persons, which will also be useful to all Christians.”

But, as printer Orazio Colutio pleaded in his petition for a privilege over works of 15th-century Spanish theologian Alonso Tostado (see Sec. Brev. Reg. 355 F 2 (Feb. 20, 1595)), increasing the dissemination of works whether for popular audiences or of works “necessary to scholars but hard-to-find and then only in inaccurate editions” required “great expense of thousands of ducats, and it is therefore customary in recompense of so much effort and of such a useful undertaking and so that [the petitioners] can promptly embrace and pursue these efforts, they plead that Your Holiness will deign to accord them the grace of a privilege.” This petition makes explicit two additional justifications implicit in the general emphasis on effort and expense. First, that privileges provide a necessary incentive to the creation or dissemination of useful works, and second, that those who undertake such endeavors expect to receive a privilege. Many petitions referred to “the usual” privilege, in the “usual form” or with “the usual” remedies. See, e.g., https://www.copyrighthistory.org/cam/tools/request/showRecord.php?id=record_va_1589 (Petitions from and Privilege granted to Gerard Voss for his Latin translation of the works of St. Ephrem of Syria). Some petitions sought to bolster their cause by stressing the author’s or petitioner’s parlous circumstances. A 1599 plea by the nephew of the author of a book of Lives of the Popes affords a particularly colorful example, combining pitiful evocations of poverty with incentive arguments:

Because . . . everything has gone to pay the debts which still have not been fully paid; [petitioner] is left with only four old things, which he is unable to sell, [but] by extending to him the said privilege he will republish [his Uncle’s works] as they should be, and the privilege will encourage said petitioner to publish his Uncle’s other works and thus he will be partly acquitted of the money lent to his Uncle and of the fatal servitude [engendered by these debts].

See Sec. Brev. Reg. 290 F. 106r (petition) (Dec. 13, 1599) (petition of Alfonso Chacòn, author’s heir). See also Sec. Brev. Reg. 124 F. 288r (Oct. 3, 1586) (petition of Francesco Rocchi, miniaturist, seeking authorization to make wax medallions of the Agnus Dei, “having to support with his labors and art his poor widowed mother who is extremely poor with no [other] help, and with useless grandchildren”; Sec Brev 295 F. 174r (petition) (May 15, 1600) (Francisco Rodriguez petitioning for privilege in a book he wrote on the Jubilee because, inter alia, “of being poor, virtuous, and burdened with family, as is expected of those who serve others, I wish to have some earnings from this little book,”

Many incentive arguments, particularly when made by authors (although also made by printers in similar terms) may still resonate with modern readers, and, in addition to Tempesta’s, two others are worth quoting in full. In 1601 a scholar, Ferrante Palazzo, requested a privilege for a sacred tract,

a work which will be of no small usefulness to clerics of both sexes, and which shows the path of regular religious observance, and of the [Catholic] Reform, so greatly desired and achieved with the great vigilance and solicitude of Your Holiness. And because the petitioner’s work was a labor requiring ten years, and so that others do not reap his labors, he humbly begs Your Blessedness to deign to grant him a privilege so that for the next ten years no one may print or have printed the said work, neither in the language in which the author will publish it nor in any other language in which it may be translated, without the permission of the author or of his heirs, all of which he will receive through the grace of Your Holiness, and which will encourage him to bring forth other fruits of his labors for the benefit of the public.

Sec. Brev. Reg. 304 F. 273r (petition) (Jan. 23, 1601). Palazzo’s public benefit argument very explicitly ties his claim to the advancement of the Counter Reformation. He bases his claim not only on reward for past labors (and fear of their misappropriation), but also on the enhanced likelihood of his creation of future beneficial works, should the Pope reward the current work with a privilege. The scope of the petition is also worth noting, for it anticipates that the work will be translated. While it does not appear that the author has himself translated or authorized foreign language versions, he could well have expected that foreign language versions would be in prospect, particularly given the proclaimed utility of the work to the Counter Reformation, and therefore he wants to ensure that all future translations come within the scope of his grant of exclusive rights. As formulated in the petition, the rights over future translations are part of the author’s incentive package.

In 1598, Fabrizio Mordente, a mathematician from Salerno, sought a privilege for his Propositions of Geometry:

It seems appropriate that those who exert themselves in study for the benefit of others shall also be recognized and rewarded for their efforts at least with prerogatives so that these same people will more willingly bind themselves to greater labors and so that others will be inspired to similar efforts. Wherefore Fabrizio Mordente of Salerno, the most devoted petitioner of Your Holiness, having through long study and great effort over many years, devised seven Geometric Propositions with a corollary, which effort will be most useful to scholars of that profession, and desiring to publish his work for the public benefit, most humbly begs Your Holiness to deign to extend him the grace of granting him a privilege by Apostolic Letter, so that for ten years no one else, other than this petitioner and those having permission from him, may have the said work printed nor sold in any place in the Papal States, under penalty of 1000 scudi and with such provisions as in similar cases are usually granted, which this petitioner will receive through the most singular grace and clemency of Your Holiness.

Sec. Brev. Reg. 277 F. 290r (petition) (Dec. 30, 1598). Mordente has generalized the public benefit argument from the virtues of his particular work to the stimulating effects that the grant of a privilege to him will have not only on his own future creativity, but also on other authors. His rhetoric mixes entitlement for his own achievements (“par convenevole” “sean riconosciuti e premiati”) with broader consequentialist contentions (“accio et i medesimi più volontieri s’accingano a maggiori, et gli altri s’inanimiscano a simili fatiche”), a combination that prefigures modern copyright law’s complementary (and sometimes competing) natural rights and utilitarian rationales.

5. Persons mentioned in the petition and privilege

Marcello Vestrio Barbiani (? – 1606). Cardinal-Secretary of Brevi (papal letters). The son of a famous lawyer, Barbiani joined the Papal court after his wife, a Roman noblewoman, passed away. In 1596, he was granted a canonicate in the Vatican Basilica. Barbiani served in various capacities under Gregory XIV, Clement VIII, and Paul V, before passing at a very old age shortly before July 9th, 1606. See Giammaria Mazzuchelli, Gli scrittori d’Italia. Vol. 2,1 at 178 (1758).

Benedetto Giustiniani (1554 - 1621). Italian cardinal, born in Genoa and educated in Perugia and Padua. He was made a cardinal by Pope Sixtus V in 1586.

Antonio Tempesta, also known as il Tempestino (1555 – 1630). Italian painter and engraver originally from Florence, well known for his many etchings and engravings on subjects ranging from historical battles to hunting scenes. At the Florentine Accademia del Disegno, he studied under Santi di Tito and Joannes Stradanus before moving to Rome. In addition to his work as a printmaker, Tempesta completed commissions for various clients across Italy, including panoramas for the loggias on the third floor of the Vatican palace, frescoes in the Palazina Gambara in Bagnaia, and decorations for the Marchese Giustiniani at Palazzo Giustiniani. See also Giovanni Baglione, Le vite de' pittori, scultori, architetti, ed intagliatori, dal pontificato di Gregorio XIII. del 1572. fino a' tempi di papa Urbano Ottavo. nel 1642 314-16 (Rome 1642) (short piography of Tempesta); Michael Bryan, Dictionary of Painters and Engravers, Biographical and Critical, Volume II: L-Z 556 (Walter Armstrong & Robert Edmund Graves eds., 1889).